Project

Right to Land for Marginalised People

-

Amount Funded

192,982 EUROProject Duration

01 Sep 2018 - 29 Feb 2020 -

-

Lead organisation

Yayasan Bumi Manira (Bumi Manira Foundation/YBM)

-

Yayasan Bumi Manira (Bumi Manira Foundation/YBM) provides support and services to development agencies in communication, development of materials including participatory approaches and methodologies for community development and natural resources management.

YBM is one of the leading agencies of the Nusa Tenggara Community Development Consortium (NTCDC), a dryland farming program which seeks to look into issues of food security, soil and water conservation which is one of the disaster mitigation methodologies such as landslides and drought.-

Organisation

Yayasan Bumi Manira (Bumi Manira Foundation/YBM) provides support and services to development agencies in communication, development of materials including participatory approaches and methodologies for community development and natural resources management.

YBM is one of the leading agencies of the Nusa Tenggara Community Development Consortium (NTCDC), a dryland farming program which seeks to look into issues of food security, soil and water conservation which is one of the disaster mitigation methodologies such as landslides and drought. -

Project

Right to Land for Marginalised People project aims to increase the community’s resilience in 6 villages in Sumba through sustainable social capacity. The project seeks to ensure that marginalised communities particularly households headed by women, get access to and control of cultivation land as long-term household income as well as the Implementation of natural resource management in the village, with sustainable social political support.

The project method consists of awareness building, negotiation, and conflict mediation so that all stakeholders agree to open access to land. Among the tools utilised is participatory mapping of land boundary, status, ownership, and its allocation.

-

-

Right to Land for Marginalised People project aims to increase the community’s resilience in 6 villages in Sumba through sustainable social capacity. The project seeks to ensure that marginalised communities particularly households headed by women, get access to and control of cultivation land as long-term household income as well as the Implementation of natural resource management in the village, with sustainable social political support.

The project method consists of awareness building, negotiation, and conflict mediation so that all stakeholders agree to open access to land. Among the tools utilised is participatory mapping of land boundary, status, ownership, and its allocation.

-

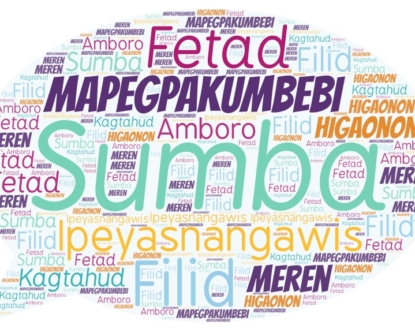

Most of the land in the villages in Sumba Tengah and Sumba Timur Districts in Indonesia is owned by the Maramba caste (the aristocrats) and is passed by inheritance while people of the lowest caste, Ata (the servants), as well as other poor communities, have no access to land for cultivation. The servant caste is exploited as labourers without the right to benefit from the land they manage. Their lives depend on the “mercy” of the master. In addition, community lands in some villages are “claimed” as national parks or industrial plantations, limiting access for those who depend on the forest for subsistence. Despite the large swathes of unused land in these districts, poverty, malnutrition, and low food security are still prevalent. The situation is made worse by this strong social caste system.

In general, Sumba culture knows 3 social classes, namely Maramba (the aristocrats), Kabihu (the ordinary people), and Ata (the servant) – this social status is inherited and has remained rigid. There is a sharp contrast between the Maramba and Ata caste, the first has full control economically, socially, and culturally through external and internal authority and institutions, while the latter fully depends on the first. For the Maramba, servants are a symbol of status, although exploiting and escaping the responsibility to take care of their lives is a common practice.

In the public sphere, these marginalized people have no opportunity to share different opinions in front of the superior caste or in an open forum as they are deemed not knowledgeable enough to make decisions and thus, rarely get important positions in the village. Women tend to be the most marginalized and women servants are vulnerable to violence from both males and females from the upper caste. In addition, the culture of polygamy is rampant and husbands can marry other women without consent from their wives.

Yayasan Bumi Manira (Bumi Manira Foundation/YBM) is a non-profit organization that was established in 1987 and has been providing support and services to other development agencies in Indonesia, and abroad. YBM has been implementing the project “Right to Land for Marginalized People” whose aim was to increase the community’s resilience in 6 villages in Sumba through sustainable social capacity development. It sought to enable marginalized communities to get access to and control of land cultivation as long-term household livelihood and implement natural resource management in the village, with sustainable social and political support.

The project is expected to initiate policy change, both on customary law level as well as state law, to ensure equal access to land and its harvest for every villager, including women as heads of households. The project approach consisted of awareness building, negotiation, and conflict mediation so that all stakeholders agree to open access to land. Among the tools utilized by YBM was the participatory mapping of land boundary, status, ownership, and its allocation.

“We appreciate Voice’s project management system, which provides freedom to grantee to implement various approaches or method. Concerning advocacy, to reach bigger scale of advocacy impact to district level, province, or national level, we need long term period. Our project used evidence base advocacy, because its effective to influence multi stakeholder and reach social change. Actually, our project still in collect evidence base stage.” – project final report

The project has resulted in 30 marginalized people (17 men and 13 women, of which 13 are Ata people, 12 migrants, and 5 women-headed households) from all 6 villages of project locations having access to the land of an average of 1.4 hectares per household for their farmland and long-term livelihoods. They have also been involved in the activities outside of their home, in the farmer groups, in the village meetings, and some people have presented to their communities at district level meetings.

The project’s participatory action research (PAR) approach that integrates cultural approaches in building their awareness was an innovative approach that proved quite successful in influencing community attitudes and views on the importance of land access for marginalized people. This was an important learning component of the project, especially after a learning visit to Mogomogo and Gerodhere Villages in Nagekeo District, Flores where the village government in collaboration with traditional local leaders have been successful in distributing customary lands to marginalized people. This approach succeeded in influencing and shaping constructive engagement between Maramba and land authorities to provide access to land for marginalized people. The use of participatory techniques makes it easy for everyone to be actively involved in carrying out an objective analysis of the social and economic conditions of society. All participants involved were able to examine their own existence, thereby raising new awareness of the existence of social and economic inequalities due to the prevailing social strata in the village community.

Most Significant Change: The most significant change that the project observed occurred as a result of its intervention is the existence of four key agreements. This change is very significant because five traditional leaders, one person in the Prailangina Preparation Village, two people in Wunga Village, and one person in the Matawai Pawali Village are the first to provide access to land management to the community, including the marginalized. They have strong authority and influence in the distribution and management of communal lands. Without the willingness of these traditional leaders, the objectives of the project would not have been achieved. Meanwhile, the the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry and Environment, a state institution that has the authority to grant community forest management permits, issued an IUPHKm . Without an IUPHKm, the community cannot access forest land.

The first agreement was between the Kabihu (Customary Land Controllers) and the village community (195 people) including the marginalized people in Prailangina Hamlet of Napu Village, Haharu Sub-district, East Sumba District. The second and third agreements were between private land owners (two persons) and marginalized people in Wunga Village (20 people) of Haharu Sub-district, East Sumba District. The fourth agreement was the issuance of Decree of Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) number SK.8465/MENLHK-PSKL/PKPS/PSL concerning Establishment of Community Forest Management Business Permit (IUPHKm) for 56 people. The Decree was issued on October 19th, 2019 signed by Dr. Ir. Bambang Supriyanto, M.Sc., the Director General of Social Forestry and Environmental Partnership (Perhutanan Sosial dan Kemitraan Lingkungan/PSKL) of the (MoEF). The land was zoned for community forestry use and is located at Lai Kanjuruk Watu Kuci Permanent Production Forest Zone at Matawai Pawali Village, Lewa Sub-district, East Sumba District, East Nusa Tenggara Province.

The people who were involved in the change are the tribal or traditional leaders of each village (Prailangina-Napu Village and Wunga Village), marginally accessing land of 119 households of tribal land and private land, Chief of the Matolang Tribe, Matawai Pawal Village, Matawai Pawali Village Farmer Group and Technical Implementation Unit (Unit Pelaksana Teknis/UPT) of the Environment and Forestry Sector of East Sumba Distrit, and Friends of Humba Hamu in the three villages, and the Government of Prailangina, Wunga, and Matawai Pawali Villages.

The ultimate impact of the project in terms of improving people’s living condition, when compared with the project objectives showed that, two out of four project objectives were adequately fulfilled- the area of land distributed and the target of village spatial planning. Two others objectives- percentage of marginal household who get access to the cultivated land are women headed household, and a percentage of marginal household (30% who are women) have a farming plan, were partially met. On the other hand, there is one impact that was not initially anticipated, the involvement of several Ata people and people with disabilities in several project activities at the district level and outside of Sumba Island level.

The distribution of farm and residential land certificates to 100 households in Matawai Kurang Hamlet of Bidihunga Village, Lewa Sub-district, East Sumba District has provided certainty for some of the rightsholders in terms of their rights to farming activities. This triggered collective actions among the people within the hamlet to construct water system to residential areas by using hydram pump technology.

The submission of Community Forestry Management Permit (Ijin Usaha Pengelolaan Hutan Kemasyarakatan/IUPHKm) to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in Matawai Pawali Village, Lewa Sub-district, East Sumba District provided awareness to customary people that part of their land has been included in the forest area.

The involvement of several Ata people in the project activities (meetings, linking and learning, radio speakers) triggered an open dialogue in the communities about the existence of Ata caste who had never been considered.

Lessons Learned: The most significant lesson the project learned during the implementation of this project is that participatory mapping activities are not just about making maps. There are many conflicts that were identified during the mapping process; i.e. village boundary conflicts, land tenure conflicts between tribes and the state, and each person’s interests.

It is very rare that development programs pay attention to or challenge the existence of Ata caste – the lowest social status and marginalized people who have no access to land, since there is an assumption that it will create a resistance for Maramba caste and will be considered to be against the adat (local wisdom). The right strategy and approach are needed to accommodate not only the interest of the Ata people but also pay attention to the interest of the Maramba people.

As an outsider, the project hoped and encouraged the Ata to rebel and escape from the bondage of the Lord, so that they can be free as humans. It turned out that the relationship between Ata and Maramba is very tight, there is mutual dependence between them. The source of livelihood for the Ata is very dependent on Maramba. Because of that, obtaining the right to land for a source of livelihood became strategic in freeing the Ata people from dependence on the Maramba. Without a source of livelihood, in this case land, the Ata will be increasingly marginalized.

Managing conflicts of interest among customary elders does not always run smoothly, commitments at the beginning cannot be used as a benchmark. When they committed to the meeting, it was not certain that outside the meeting they will be consistently committed. Often there was a change in commitment between the parties, the approach must be repeated. An important strategy for unanimous commitment is to approach influential figures who want to distribute land.

Carrying out budget advocacy to farmer groups must really pay attention to the readiness of farmer groups in managing administration and finances. The commitment and seriousness of the farmers’ groups is not a guarantee, when the capacity and administrative and financial systems are not controlled and run together.

Finally, the project learned that in formulating rules, especially in pandemic conditions, one cannot be rigid. Indonesia is very big. The infrastructure facilities of different regions vary significantly. The activities in the field need high flexibility. The utilization of gadgets and the internet are not the only way to overcome communication barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic. There are many signal and resource constraints to apply in remote areas.

-

News