Project

HUMANITY for Conflict Survivors

-

Amount Funded

185,523 EUROProject Duration

01 Sep 2018 - 31 Aug 2020 -

-

Lead organisation

-

Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR) is a non-profit organisation registered in Indonesia, whose aim is to contribute to the strengthening of human rights and the alleviation of entrenched impunity in the Asia-Pacific region. AJAR focuses on countries involved in transition from a context of mass human rights violations to democracy. It strives to build cultures based on accountability to help prevent the recurrence of state-sanctioned human rights violations.

AJAR achieves its goals through empowering key individuals and groups who are involved in the long-term struggle for truth, accountability, and justice in their national contexts. AJAR does this through:

• trainings, exchanges, and strengthening networks to increase the knowledge and capacity of survivors, human rights defenders, and government officials;

• research to establish and share the truth concerning mass human rights violations using participatory methods;

• utilise research results in advocacy to national, regional, and international organizations;

• increase popular, broad-based understanding of human rights, justice, tolerance, gender equity, etc. through use of mass media;

• contribute to the empowerment of women survivors and human rights defenders so that their voices have an increased impact on policy and practice.AJAR has a unique contribution to human rights in Indonesia. They are a global south NGO with regional and international experience, but also strong relationships based on trust with local partners and survivors’ communities. AJAR has a commitment and understanding that justice is a long process that requires building social movements in each context that has experienced the violations.

-

Organisation

Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR) is a non-profit organisation registered in Indonesia, whose aim is to contribute to the strengthening of human rights and the alleviation of entrenched impunity in the Asia-Pacific region. AJAR focuses on countries involved in transition from a context of mass human rights violations to democracy. It strives to build cultures based on accountability to help prevent the recurrence of state-sanctioned human rights violations.

AJAR achieves its goals through empowering key individuals and groups who are involved in the long-term struggle for truth, accountability, and justice in their national contexts. AJAR does this through:

• trainings, exchanges, and strengthening networks to increase the knowledge and capacity of survivors, human rights defenders, and government officials;

• research to establish and share the truth concerning mass human rights violations using participatory methods;

• utilise research results in advocacy to national, regional, and international organizations;

• increase popular, broad-based understanding of human rights, justice, tolerance, gender equity, etc. through use of mass media;

• contribute to the empowerment of women survivors and human rights defenders so that their voices have an increased impact on policy and practice.AJAR has a unique contribution to human rights in Indonesia. They are a global south NGO with regional and international experience, but also strong relationships based on trust with local partners and survivors’ communities. AJAR has a commitment and understanding that justice is a long process that requires building social movements in each context that has experienced the violations.

-

Project

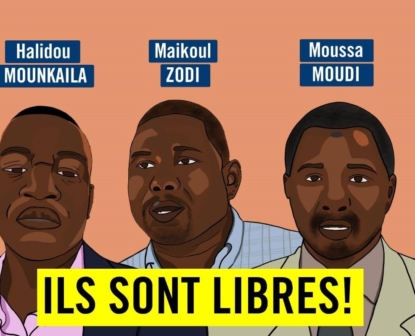

Two decades after the end of Soeharto’s dictatorship, many past atrocities in Indonesia remain unresolved. This includes the 1965 anti-communist violence affecting more than 500,000 people, and the lesser known issue of the “stolen children” of Timor-Leste. They were forcibly removed from their families and brought to Indonesia during the conflict of 1975-1999.

Years, if not decades, have passed without redress for the survivors, some of whom are elderly, have physical disabilities due to violence, and face further stigmatisation as ethnic minorities. Most survivors’ voices are still silenced and unheard. Their children face the intergenerational impact of violence and are in need of emancipatory tools to access urgent needs of justice and social services.

This project seeks to empower women survivors of the 1965 anti-communist violence, the stolen children of Timor-Leste, and the survivors’ children, through youth-led participatory action research (PAR) that encourages survivors to learn from their painful past, identify their needs, and draw from their strengths in order to increase their decision-making power and access to urgent needs. The project seek to review and deepen the methodology AJAR has used and scale up the methodology in other areas of Indonesia, bringing new target groups into the fold.

The project HUMANITY for conflict survivors consists of trainings for youth survivors in PAR processes and multimedia production, a series of youth-led PAR processes that incorporate multimedia tools to document the stories of conflict survivors, a dialogue series with local authorities, and a parallel offline and online multimedia exhibit based on the data collected by youth survivors for the public sphere.

At the end of the project, survivors and their children have made their stories heard and increased their agency for change in the public sphere and among local authorities, while strengthening their capacity for healing, intergenerational solidarity, and mobilisation towards an intersectional survivors’ movement.

-

-

Two decades after the end of Soeharto’s dictatorship, many past atrocities in Indonesia remain unresolved. This includes the 1965 anti-communist violence affecting more than 500,000 people, and the lesser known issue of the “stolen children” of Timor-Leste. They were forcibly removed from their families and brought to Indonesia during the conflict of 1975-1999.

Years, if not decades, have passed without redress for the survivors, some of whom are elderly, have physical disabilities due to violence, and face further stigmatisation as ethnic minorities. Most survivors’ voices are still silenced and unheard. Their children face the intergenerational impact of violence and are in need of emancipatory tools to access urgent needs of justice and social services.

This project seeks to empower women survivors of the 1965 anti-communist violence, the stolen children of Timor-Leste, and the survivors’ children, through youth-led participatory action research (PAR) that encourages survivors to learn from their painful past, identify their needs, and draw from their strengths in order to increase their decision-making power and access to urgent needs. The project seek to review and deepen the methodology AJAR has used and scale up the methodology in other areas of Indonesia, bringing new target groups into the fold.

The project HUMANITY for conflict survivors consists of trainings for youth survivors in PAR processes and multimedia production, a series of youth-led PAR processes that incorporate multimedia tools to document the stories of conflict survivors, a dialogue series with local authorities, and a parallel offline and online multimedia exhibit based on the data collected by youth survivors for the public sphere.

At the end of the project, survivors and their children have made their stories heard and increased their agency for change in the public sphere and among local authorities, while strengthening their capacity for healing, intergenerational solidarity, and mobilisation towards an intersectional survivors’ movement.

-

Two decades after the end of Soeharto’s dictatorship, many past atrocities in Indonesia remain unresolved. This includes the 1965 anti-communist violence affecting more than 500,000 people, and the lesser-known issue of the “stolen children” of Timor Leste. They were forcibly removed from their families and brought to Indonesia during the conflict of 1975-1999. Years, if not decades, have passed without redress for the survivors, some of whom are elderly, have physical disabilities due to violence, and face further stigma as ethnic minorities. Most survivors’ voices are still silenced and unheard. Their children face the intergenerational impact of violence and are in need of emancipatory tools to access urgent needs of justice and social services.

Asian Justice and Rights (AJAR) is an organization that works with target groups, particularly victims’ groups and survivor communities, to co-develop activities and programs based on the needs of survivors and their communities. AJAR also builds a multi-layer relationship with local civil society organizations and victims’ organizations that commit to working with survivors. It is notable that many of their Participatory Action Research (PAR) facilitators in the past are also survivors of conflict who are program participants. For instance, AJAR’s volunteer to trace Timorese stolen children in Indonesia and reunite them with their families in Timor Leste is himself a stolen child.

AJAR approach is to interact with rightsholders, encouraging their insights, wisdom, and strategies to shape joint activities. For instance, AJAR has worked with a group of Papuan women survivors in Manda Village, Wamena, training them to become PAR facilitators. Since then, this group of women have designed women’s empowerment projects such as communal noken (traditional bag) weaving networks. All the while, AJAR provides programmatic support for the Papuan women facilitators to successfully implement their projects. AJAR has and will continue to maintain the same kind of empowering, mutual working relationship with the local partners identified in this project.

The project Harnessing Understanding, Mobilizing ActioN in Indonesia Through Youth (HUMANITY) for Conflict Survivors is a project that seeks to empower women survivors of the 1965 anti-communist violence, the stolen children of Timor-Leste, and the survivors’ children, through youth-led participatory action research (PAR) that encourages survivors to learn from their painful past, identify their needs, and draw their strengths in order to increase their decision-making power and access to urgent needs. Building on AJAR’s participatory action research in Indonesia, Timor Leste, and Myanmar, it sought to review and deepen the methodology in areas where it had started implementing the process (for instance, in East Nusa Tenggara with 1965 women survivors) and scale up the methodology in other areas of Indonesia (Jakarta, West Java, Central Java, South Sulawesi), bringing new target groups (Timorese stolen children and children of survivors) into the fold.

Through PAR, the capacity of survivors was strengthened, especially the capacity of trafficked survivors. The facilitators invited survivors to formulate ideas and develop action plans. This helped survivors gain confidence and courage to speak to village authorities.

After conducting a meeting with young people, a survivor in Central Java commented: “I continue to live today because I have met with young people who will continue to spread the truth and continue the revolution”- Bung Muchran (victim of the ‘65 Incident from Central Java).

HUMANITY was able to engage with local government apparatus, including BPDs, or village representative bodies, and village heads. Specific examples include engaging with village heads in the district of Bokong in East Nusa Tenggara on human trafficking issues, and in Palopo in South Sulawesi on support for ‘stolen children’. AJAR understands the importance of engaging with local governments, and will continue to focus on this challenge in its future work, exploring new and innovative approaches.

Through its ‘unlearning impunity’ approach, AJAR encouraged survivors and their communities to identify their strengths and weaknesses, and to map their resilience or coping mechanisms, in relation to the impact of violence. The approach helped victims build solidarity, identify needs, and develop advocacy strategies. ‘Unlearning impunity’ acknowledges deep cultural, political, and socio-economic roots in the justice process that often impacts disproportionately on poor and disenfranchised people and communities. The approach not only builds solidarity between generations, but also builds cross-sectoral networks, including victims of human rights violations with young facilitators and artists, and human rights defenders and activists. AJAR involved non-activists, like curators and young artists, in developing learning products from the participatory research findings. Collaboration between groups of young people made HUMANITY a safe learning place, helping to understand that impunity in Indonesia impacts victims of human rights violations across generations.

- News