Indonesia

Grant distribution

Latest Voices

Open Calls for Proposals

39 Empowerment grants

39 Empowerment grants  15 Influencing grants

15 Influencing grants  12 Innovate and learn grants

12 Innovate and learn grants  5 Sudden opportunity grants

5 Sudden opportunity grants -

No Open Calls at the moment in this country. Come back later!

-

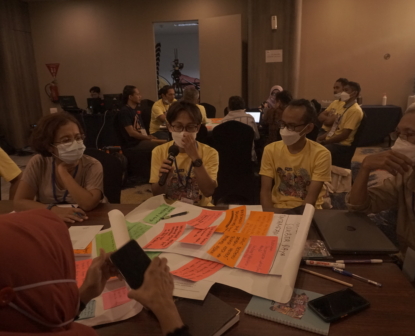

Indonesia is one of the four Southeast Asian countries where Voice is active. Hivos coordinates the Voice programme here. We live in a rapidly changing world – some changes may be for the better – others not so much. In order to continue to ground Voice in local lived realities, a country context analysis is organised every other year, engaging many stakeholders, grantees and rightsholders. The analysis is used to frame Calls for Proposals, to support the applications of grant-seekers and to advance the overall learnings. Below follows a summary of the exercise conducted in 2022, capturing the many views and perspectives of Indonesians. The summary is structured by presenting the big picture and slowly but surely to zoom in on the voices and aspirations of the rightsholders and to zoom out again by sharing the way forward for Voice. This page can also be downloaded at the bottom of the page. A full report and previous versions can be availed to you upon request. Please contact Indonesia@voice.global

Zooming out

The big picture

-

The Human Development Index is an index that combines data on life expectancy, education, and per capita income to rank countries. HDI ranking has slightly improved between 2016 and 2019 but unfortunately, this hasn't translated into a better standard of living for many rightsholders concerned.

-

The IHDI measures the human development cost of inequality, or the overall loss to human development due to inequality. The closer to 1 the more equal a society is. The IHDI can inform policies towards inequality reduction. Inequality has lessened slightly between 2016 and 2019 but is still a persistent problem for many of the groups Voice works with.

-

The GII is an inequality index, measuring the human development costs of gender inequality economically, health- and education-wise. The closer to 0 the better. While on the surface it looks like gender equality has improved it continues to be challenged in the country with new laws impacting women’s access to justice and reproductive rights.

-

According to the independent Civicus Monitor which started in 2016, civic space continues to be obstructed in Indonesia. Civic space continues to be obstructed especially on issues related to LGBTI rights. West Papua also continues to face human rights violations and civil repression as they continue to fight for their independence.

Behind the numbers

A major shift between the years 2020 and 2022 has been caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which severely impacted the lives of the population, particularly rightsholders in vulnerable communities. While Indonesia and its neighbouring countries rolled out timely vaccination campaigns, the pandemic’s curbs on the economy and society continue to have a significant impact on human development. Beyond the public-health crisis caused by the pandemic itself, restrictions on the society are pushing many people into poverty, while further exposing the exclusion and discrimination of intersectional rightsholders regarding their social, economic, and health situation. Many lost their sources of income for basic needs, face increased health risks, and were further excluded from participating in political processes. On a positive note, Indonesia is one among 80 countries that has substantially improved on the Healthcare Universalism Index (HUI).

Political shifts

In the years since 2016, democratic freedoms in Indonesia have waned slowly but noticeably. Using the COVID-19 crisis as a pretext to uphold social distancing regulations, the government discouraged and eventually ignored societal protests against some of its policies seemingly. Several controversial laws were pushed through the parliament in 2020 that would have been difficult to pass without the restrictions put in place due to COVID-19. Among them was the Omnibus Law on Job Creation that was strongly opposed by rightsholders, labour unions, environmentalist, feminists, activists, Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) and indigenous communities across Indonesia. The government also made more use of the revised Law on Mass Organisations, which allows to ban any organisation on ideological grounds.

The Indonesian Constitution guarantees freedom of religion. This right, however, has been increasingly weaponised against rightsholders. One indication of this is the rise in the number of blasphemy cases that implicate vulnerable rightsholders such as Sexual and Gender Minorities (SGM), including Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersexual (LGBTI) people as well as indigenous groups and ethnic minorities.

In most parts of Indonesia, the freedom of association and assembly is generally upheld, but there are important exceptions, which have increased in severity. First, groups advocating for the separation of their territory from Indonesia have been systematically repressed. Second, left-wing activism has been increasingly discouraged and prosecuted. Third, non-mainstream religious and social groups (such as Ahmadis, Shi’ites, or SGM) enjoy no protection of their rights to assembly and association. Their meetings are often disbanded, and their members assaulted, both by societal groups and law enforcement agencies. Fourth, indigenous groups and environmentalists are often persecuted and labelled as anti-governance (pembangunan).

Economic shifts

The Indonesian economy during the pandemic years slowed down to negative 5.3 percent in the second quarter of 2020 and aggregate growth fell to negative 2.1 percent from 2020 to 2022. The target of development planning in the National Medium Term Development Plan 2020-2024 was revised through the updating of the Government Work Plan in 2020, with the main priority of overcoming COVID-19.

The main effect of the pandemic-induced changes is that a new wave of households, which were previously economically secure, have now become more vulnerable. After years of progress, poverty is rising again, with one in ten people in Indonesia today living below the national poverty line. Women who acted as primary earners for their households continued to work, but some were working fewer hours and earning less, with the added burden of supervising their children who shifted to online learning alongside domestic and care work. This has led to burn out and created risks to mental health. These and other long-term impacts on the quality of human resources in Indonesia will ultimately affect its poverty rate.

Social shifts

The law prohibits discrimination in employment and occupation, but not specifically with respect to sexual orientation or gender identity, national origin or citizenship, age, language, or HIV or other communicable disease status. Human rights groups reported that some government ministries discriminated against pregnant women, People with Disabilities (PWDs), SGM individuals, and HIV-positive persons in recruitment. Migrant workers and PWDs commonly faced discrimination in employment and were often only hired for lower-status jobs.

Some indigenous groups experience stigma related to caste-like social stratifications, while others are excluded because of their geographical remoteness. Some religious minorities are stigmatised because they are viewed as a threat by mainstream religions, while others face stereotypes of being ‘backwards’ because of their traditional beliefs. Victims of past human rights violations are often themselves ashamed of their status, and those who speak out are often quickly silenced. All groups experience harassment, and some face open hostility when they attempt to form solidarity groups among their members, particularly SGM and religious minorities.

Forced labour occurred in domestic work settings and in the mining, manufacturing, fishing, fish processing, construction, and plantation agriculture sectors. No legal protections have been put in place to ensure labour rights, such as limiting working hours, occupations, or tasks for women workers.

(Visible) power shifts

Corruption and abuse of power remain endemic and the protection of civil rights remained volatile in Indonesia in 2022. Normativity, religious conservatism, and traditional gender roles still have invisible power leading to discrimination. Followers of non-mainstream religious groups, left-wing activists and pro-independence campaigners continued to experience severe violations of their civil rights, both by the state and other members of society. Traditional gender roles are still used to justify violence in the household or immediate community and authorities and influential radical Muslim organisations continue to intimidate and harass LGBTI activists. The LGBTI activist community has been driven underground and groups seeking to provide services to LGBTI people are hampered in their efforts to reach out.

Activists working to address human rights violations and to expose endemic corruption in the country are often targeted by authorities or pro-government supporters. There are also growing concerns that the government has used the COVID-19 pandemic to tighten restrictions on journalists, including criminalising criticism of the government. Journalists covering sensitive subjects – including LGBTI issues, organised crime, and corruption – face harassment, violence, and threats. Feminist media reported online bullying and violence during the pandemic.

Covid-19 related shifts

The second COVID-19 wave surged in Indonesia in mid-2021, prompting the government to implement further lockdowns while trying to maintain equal opportunities to access health services, education, public office, or employment. Vulnerable rightsholders experienced a disproportionate negative impact from these measures.

The low quality of the public health care infrastructure made it difficult for the government to respond effectively to the pandemic. Due to lack of suitable laboratories in its public health domain, Indonesia had one of the lowest testing rates in the world by 2021. The fundamental strategy for hospitals and health workers has been for essential core health services to be intensified to deal with COVID-19 cases. However, the country struggled to prevent community transmission. The high number of health worker deaths due to COVID-19 invited speculation on health workers’ job insecurity, insufficient health supplies, and inadequate health facilities and resources.

In the same vein, the government initially struggled to get social assistance to recipients, a circumstance aggravated by corruption in the bureaucracy charged with distributing social assistance. Additionally, the growing influence of the military over civilian governance and economic affairs could be gauged from the fact that military generals served as the heads of both the National Task Force for COVID-19 Management and the Ministry of Health at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Out of the 40 COVID-19 policies implemented by the government, only 13 are ‘gender-sensitive’ according to the global gender response tracker. Most of these measures relate to violence against women and girls (VAWG), economic security or unpaid care, but often did not address specific needs of adolescent girls. In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the government increased the state budget to provide funds for healthcare, social protection, and businesses. However, all measures did not consider a gender analysis. Moreover, PWDs stated that information and awareness raising related to the prevention of the spread of COVID-19 was not at all accessible to those with visual and hearing impairments.

Social stigma has also negatively affected social justice for COVID-19 survivors because a stigmatised person cannot actively participate in society. Some survivors have suffered severe mental distress even after discharge and rehabilitation.

The COVID-19 pandemic also drove digitalisation in various aspects of life. However, inequalities in access to digital infrastructure and differing rates of digital literacy contributed to widening the gap as well as increasing vulnerability of the rightsholders, which triggered economic and social exclusion.

Shifts in policy design and implementation

For Youth, the planning of the Youth Friendly City policy by Indonesian Ministry of Youth and Sports is expected to strengthen youth development and empowerment in each region of Indonesia. For the Elderly, at the national level, the government has included the elderly as beneficiaries of the Family Hope Programme (Program Keluarga Harapan: PKH).

The issues facing Indigenous People become even more complex with unsynchronised regulations. The Omnibus Law on Job Creation has the potential to threaten their habitat. Meanwhile, the Bill for the Indigenous Peoples’ Law has not been ratified. Ratification of this Bill would ensure the synchronisation of various regulations and can eliminate conflicts within indigenous areas.

For Sexual and Gender Minorities, the government has postponed the controversial revised criminal code. In May 2022, however, the call to raise the bill has been sounded again by conservative groups and their political allies. The coordinating Minister for Political, Legal and Security Affairs emphasised that the prohibition on LGBT people has been included in the draft Criminal Code Bill (RKUHP) on 18 May 2022.

The Omnibus Law also discriminates against People with Disabilities with the use of the term “cacat” or handicapped which is a major step back in the progress Indonesia has made in the past ten years. The law discriminates against PWDs in access to hospitals and access to reasonable adjustment in the workplace.

By the end of 2021, there were 441 policies that were discriminatory against Women and intersectional rightsholders. The Law on Sexual Violence Crimes was finally enacted by People’s Representative Council on 12 April 2022 after 8-years of prevarication. The law will better protect PWDs, especially women and children, from different forms of sexual violence.

Zooming in

Voices behind the picture

The civic space in Indonesia is becoming further obstructed due to increasing exclusion, threats to the freedom of expression and of people assembly, and acts of persecution of rightsholders. Regarding the current shifts in the country, the five rightsholder groups of Voice are among the most vulnerable and most discriminated population groups.

As for vulnerable elderly, the pandemic has increased risks and vulnerabilities due to: 1) limited mobility during the implementation of the ‘stay-at-home’ policy which prevented them from accessing basic services, including health services; 2) acute numbers of the elderly facing lack of access to minimum income support/pension and experiencing higher rates of poverty, including greater vulnerability to the economic shock of the pandemic; and 3) increased social exclusion and isolation which could also result in, or contribute to, increased depression, fears, and feelings of helplessness.

As for vulnerable youth, most rural and poorer households faced more barriers in accessing digital infrastructure, including lack of strong internet connections and absence of devices. Furthermore, youth with disabilities who require more specialised support to enable them to learn, cannot get this support from parents at home. The critical impact of these constraints is learning loss. School closures, social isolation combined with economic uncertainties also exposed youth to other risks, including mental health concerns. Some youth in correctional facilities have limited or no access to educational and vocational programmes and may become isolated from their families due to the cost of visits. Moreover, increased numbers of street youth were observed during the pandemic crisis engaged in a variety of activities, including busking and begging on the street, and providing informal services in markets.

Indigenous Groups and Ethnic Minorities experience exclusion due to geographical isolation, barriers to indigenous rights and stigmatisation by external groups. This can result in barriers to civil rights (particularly legal identity), education, health services, livelihoods, social welfare services, and job opportunities. Within their own communities, they can enjoy freedom of expression and religious expression, but they also experience intimidation and violence from external groups, including corporate actors, and violence from security personnel, particularly when land tenure is at issue. Indigenous Groups and Ethnic Minorities are often seen as vulnerable due to their lifestyles being different from modern customs. Additionally, policy enactments made during the pandemic compounded this vulnerability further by scaling back protection for them.

Since January 2018, as part of revisions to the Criminal Code, lawmakers have been working on a draft law to criminalise consensual sex between two unmarried people, cohabitation, adultery, and rape. The proposed law would also allow Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) people to be prosecuted in court for their sexual orientation and gender identity. Despite the national and international criticism and protests from human rights organisations, the passing of the Criminal Code could become major a threat for Sexual and Gender Minorities (SGM) in the future. Authorities and influential Muslim organisations continue to intimidate and harass SGM people and activists. Consequently, they experience barriers to civil rights (particularly legal identity) often because of being unable to access official documentation held by their families, from whom they may be estranged. There appears to be no explicit barriers to health services, but self-exclusion occurs. This also applies in relation to access to mental health services.

The experience of People with Disabilities (PWDs) in Indonesia is often one of rejection and stigmatisation. The economic impacts brought hardships to PWDs due to 1) lower education levels, 2) less access to the labour market, 3) higher costs, and 4) lower income compared to people without disabilities. The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted students with disabilities to drop-out of education. Low education attainment poses significant barriers to the labour market and consequently a low rate of labour force participation.

As for Women facing exploitation, abuse, and/or violence, the COVID-19 pandemic has a significant impact on poor women, as they carry the burden of unpaid work such as care and domestic labours. In addition, the job market is requiring women to be adaptive. Women need to adapt to technological advancement while at the same time deal with the adverse impacts of digitisation of labour. Online work has not only increased domestic violence, but also caused growing mental health issues as women must bear double or triple burden.

Their aspirations

A key aspiration of Elderly rightsholders is to for the social protection programme to be strengthened by promoting a simple registration process and employing a risk-sharing approach. The risk sharing approach would entail increasing collaboration between central and local government with NGOs, the private sector, and international organisations as well as community funds.

For Youth, the key aspiration relates to the educational sector. Especially, in rural, remote areas, youth want to be prepared to enter the job market for long-term employment or to become self-employed. Additionally, sexual and reproductive health related information also needs to be urgently included in school curricula.

Indonesia is home to the third-biggest swath of tropical rainforests in the world, where an estimated 70 million indigenous groups are living. For Indigenous Groups and Ethnic Minorities, their aspirations are enhancing government’s promise to protect their rights by recognising their ancestral right, giving greater access to managing their forest, and advocating for indigenous youth’s right to learn the indigenous religions.

For Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex (LGBTI) people, their aspiration is to have a more inclusive Indonesia where importance is given to working with a human rights-based approach. Such an approach would ensure safety and security of civil society organisations, strengthen their capacity, encourage educational activities about SOGIESC issues that include their families, strengthen networking activities and collaboration with non-governmental institutions, and strengthen human rights advocacy networks for active participation in various dialogues and coalitions.

People with Disabilities aspire for strengthened access to social protection, improved communications campaigns and registration mechanisms, as well as for improved accessibility to remote learning and mainstream inclusive education.

The situation of Women facing exploitation, abuse, and violence has remained challenging throughout the years in Indonesia. It is therefore, key to support the younger generation especially around youth education on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR), as well as advocating and pushing relevant stakeholders and legislatives to ratify the Bill on the Protection of Domestic Workers to ensure protection and provide legal certainty to domestic workers.

Emergent collaborations

Universities show potential to produce new ideas on inclusion, lead research, and become agents of change. Youth movements and women’s movement, as well as the Islamic boarding school (pesantren) are key stakeholders in preventing the impact of radicalism among vulnerable youth and women. An inclusive platform must be made accessible to the youth, especially as not all have the capability to access such platforms such as young PWDs, Indigenous Groups and Ethnic Minorities. A collaboration among CSO actors, universities, small and medium businesses, cooperatives and start-ups, and social enterprises is necessary to promote entrepreneurship and youth acceleration in the digital era.

Based on the previous mapping, stakeholder and rightsholder group collaborations can contribute to the amplification of rightsholders’ interests by influencing policies or push for social change at the local and national levels. Advocacy success on the passing of Anti-Sexual Violence Bill in April 2022 advanced protection for women with disabilities and LGBTI people. Another form of collaboration is the successful cooperation between Komnas HAM (National Human Rights Commissions) and Sexual and Gender Minorities groups. Protests rejecting the Omnibus Law in several cities were a collaboration of various actors. Although not always successful, the experience of successfully pushing for the Anti-Sexual Violence Bill has boosted the confidence of activists.

Currently, indigenous community movements increasingly realise that taking over the public office in the villages is a practical strategy. Therefore, running for positions such as village chiefs or as a member of the Village Consultative Body (BPD), or making political contracts to ensure support to indigenous community rights are the steps they can carry out, especially as the 2024 general election approaches. The village can become a bulwark against indiscriminate investment projects that threaten the sustainability of ecology and the existence of indigenous communities.

Zooming out

What this means to Voice

- Promoting and strengthening visibility of all vulnerable rightsholders in post-recovery pandemic world, whether by creating opportunities for participation at the negotiating table, or providing roles, and access to social and economic service as well as political participation.

- Protection of Human Right Defenders and vulnerable groups from persecution, criminalisation, and risks of ill-health and death due to their activism.

- Strengthening the network of vulnerable elderly and youth, indigenous people and ethnic minorities network, people with disabilities’ movements, women’s movement, youth movements, Sexual and Gender Minorities, and Victims Service Providers (Pengada Layanan/Women’s Crisis Center) to advocate for cases of discrimination and violence against women with disabilities, women environmental defenders, and other vulnerable groups. This would provide victims with inclusive and accessible services in the form of accompaniment as they seek remedies through judicial processes.

- Increasing political participation of women, PWDs, the elderly, the youth, SGM, and indigenous communities and ethnic minorities in inclusive policymaking at village levels and advocating for village budgeting that mainstreams rightsholders’ interests and needs.

- Improving resources, access to livelihoods, and social coverage for rightsholders.

- Improving political participation and citizen involvement for women and vulnerable rightsholders with recently acquired disability due to COVID-19 pandemic, climate-related disaster, conflicts, and accidents.

- Improving advocacy and protection for women, youth, elderly, SGM, and PWDs from unsafe and unjust working conditions in the context of COVID-19 pandemic, as well as from the potential of deteriorating work conditions because of the Omnibus Law.

- Prioritising intersectional leadership of Youth, IGs EMs, SGM, and women in the network of collaborations in voicing inclusion and equality.

Promoting change

- The potential strategy for expanding safe and inclusive spaces for freedom of expression via policy advocacy. A key focus area can include the draft Criminal Code Bill that will endanger SGM, and advocacy against criminalisation of vulnerable rightsholders such as LGBT and human rights activists. Additional priorities areas include the National Education System Bill (RUU Sisdiknas) for enhancing access to education for Indigenous Youth, ILO Convention 190 to ensure protection of informal workers including domestic sector works, RUU KIA to not re-domesticate women, draft bill on Indigenous Community, follow-up policies on UU TPKS, RUU Perlindungan PRT, some headscarf-related discriminatory regulations across regions, and other regulations that may hinder rightsholders.

- Another key strategy is to facilitate cultural and socio-political discussions and activities led by intersectional, marginalised groups through linking and learning methods to prevent polarisation and exclusion. The rightsholder groups must continue to be connected with various civil society movements, especially social media-based youth movements, labour movements, women’s movements, and human rights and justice movements, in order to continue being exposed to enabling environments and to supporters.

- Such discussions should take place not only digitally but also offline. Geographical and technological constraints can exclude stakeholders, especially in indigenous communities and PWDs with limited access to inclusive facilities.

- The strategy of creating safe space for the empowerment of rightsholders contributes to shifting their power in society and are important investments and strategies that Voice can continue contributing to. Some examples are the safe space to gather new knowledge about their rights, to gain courage for public speaking, to develop their self-confidence, and to practice their advocacy work.

- Seizing cultural interpretation and utilising art and cultural media as an egalitarian medium for delivering messages. This is an important lesson when fighting for human rights and challenging discrimination based on gender, disability, age, sexual orientation, indigenous, cultural, religious and ethnic equality.

- Promoting advocacy to reach the policy dialogue stage, as it is important for people from rightsholder groups to guide how policy is shaped and implemented. The lived experience and self-determination of persons experiencing marginalisation must form the basis of the development of future Voice programmes about rightsholders.

-

-

Grants

-

Grantee

![Academy for the Elimination of Sexual Crimes]()

Academy for the Elimination of Sexual Crimes

LBH APIK Jakarta (Jakarta Legal Aid for Women and Children) -

Grantee

![Increasing the access of women victims of sexual violence to services for advocating derivative regulations from the Sexual Violence Criminal Act (ACCESS for SVCA Regulation)]()

Increasing the access of women victims of sexual violence to services for advocating derivative regulations from the Sexual Violence Criminal Act (ACCESS for SVCA Regulation)

LRC-KJHAM (Legal Resources Center for Gender and Human Rights) -

Grantee

![Open Arms – Towards Inclusivity in Indonesian Art]()

Open Arms – Towards Inclusivity in Indonesian Art

Selasar Sunaryo Foundation (Yayasan Selasar Sunaryo or YSS) -

Grantee

![Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth]()

Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth

International Indigenous Peoples Movement for Self Determination and Liberation (IPMSDL) -

Grantee

![Improving access to employment and the protection of women workers with disabilities]()

Improving access to employment and the protection of women workers with disabilities

Perkumpulan SEHATI Sukoharjo -

Grantee

![FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking]()

FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking

International Womens Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific (IWRAW Asia Pacific) -

Grantee

![Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures]()

Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures

International Women's RIghts Action Watch Asia-Pacific -

Grantee

![Inspire]()

Inspire

BABSEACLE Foundation host for International Drug Policy Consortium and Indonesian Act for Justice - Call for Proposal

Empowerment Accelerated!: Indonesia Empowerment Grant V-21170-ID-EM

closing date: 19 Apr 2021Closed - Call for Proposal

INCLUSION MATTERS!: Indonesia Innovate and Learn Grant V-21166-ID-IL

closing date: 31 Mar 2021Closed - Call for Proposal

Reclaiming our Civic Space!: Indonesia Influencing Grant V-20155-ID-IF

closing date: 28 Feb 2021Closed - Call for Proposal

Coming Together, Moving Forever!: Global Influencing Grants V-20152-XG-IF

closing date: 15 Jan 2021Closed - Call for Proposal

It’s Still Our Turn To Talk! Global Influencing Grant V-20151-XG-IF

closing date: 15 Dec 2020Closed -

Grantee

![Enhancing civil society participation in the deliberation of the Bill of Penal Code]()

Enhancing civil society participation in the deliberation of the Bill of Penal Code

Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR) - Call for Proposal

Indonesia Empowerment, Accelerated! – V-20139-ID-EM

closing date: 31 Dec 2020Closed -

Grantee

![Strengthening the Role of Women in Customary Institutional Structures]()

Strengthening the Role of Women in Customary Institutional Structures

Archipelago Indigenous Peoples Alliance (AMAN Sumbawa) -

Grantee

![Indigenous Youth and Women Empowerment for Livelihood Improvement and Cultural Resilience]()

Indigenous Youth and Women Empowerment for Livelihood Improvement and Cultural Resilience

Yayasan Ruang Kolektif (Common Room Networks Foundation)

Grantee![Academy for the Elimination of Sexual Crimes]()

Academy for the Elimination of Sexual Crimes

LBH APIK Jakarta (Jakarta Legal Aid for Women and Children)Grantee![Increasing the access of women victims of sexual violence to services for advocating derivative regulations from the Sexual Violence Criminal Act (ACCESS for SVCA Regulation)]()

Increasing the access of women victims of sexual violence to services for advocating derivative regulations from the Sexual Violence Criminal Act (ACCESS for SVCA Regulation)

LRC-KJHAM (Legal Resources Center for Gender and Human Rights)Grantee![Open Arms – Towards Inclusivity in Indonesian Art]()

Open Arms – Towards Inclusivity in Indonesian Art

Selasar Sunaryo Foundation (Yayasan Selasar Sunaryo or YSS)Grantee![Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth]()

Passing the torch: Land Rights Now for Indigenous Youth

International Indigenous Peoples Movement for Self Determination and Liberation (IPMSDL)Grantee![Improving access to employment and the protection of women workers with disabilities]()

Improving access to employment and the protection of women workers with disabilities

Perkumpulan SEHATI SukoharjoGrantee![FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking]()

FACT: Feminist Approaches to Counter-Trafficking

International Womens Rights Action Watch Asia Pacific (IWRAW Asia Pacific)Grantee![Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures]()

Forging Intersectional Feminist Futures

International Women's RIghts Action Watch Asia-PacificGrantee![Inspire]()

Inspire

BABSEACLE Foundation host for International Drug Policy Consortium and Indonesian Act for JusticeCall for ProposalEmpowerment Accelerated!: Indonesia Empowerment Grant V-21170-ID-EM

closing date: 19 Apr 2021ClosedCall for ProposalINCLUSION MATTERS!: Indonesia Innovate and Learn Grant V-21166-ID-IL

closing date: 31 Mar 2021ClosedCall for ProposalReclaiming our Civic Space!: Indonesia Influencing Grant V-20155-ID-IF

closing date: 28 Feb 2021ClosedCall for ProposalComing Together, Moving Forever!: Global Influencing Grants V-20152-XG-IF

closing date: 15 Jan 2021ClosedCall for ProposalIt’s Still Our Turn To Talk! Global Influencing Grant V-20151-XG-IF

closing date: 15 Dec 2020ClosedGrantee![Enhancing civil society participation in the deliberation of the Bill of Penal Code]()

Enhancing civil society participation in the deliberation of the Bill of Penal Code

Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (ICJR)Call for ProposalIndonesia Empowerment, Accelerated! – V-20139-ID-EM

closing date: 31 Dec 2020ClosedGrantee![Strengthening the Role of Women in Customary Institutional Structures]()

Strengthening the Role of Women in Customary Institutional Structures

Archipelago Indigenous Peoples Alliance (AMAN Sumbawa)Grantee![Indigenous Youth and Women Empowerment for Livelihood Improvement and Cultural Resilience]()

Indigenous Youth and Women Empowerment for Livelihood Improvement and Cultural Resilience

Yayasan Ruang Kolektif (Common Room Networks Foundation) -

-

Link + Learn

Voice Indonesia Yayasan Hivos, 18 Office Park, 15th floor, Unit B Jl. TB Simatupang No.18 Jakarta Selatan 12520 Indonesia T: 62 21 27876233 | F: 62 21 27876242 indonesia@voice.global